Diocese

The ‘Russian’ Diocese of Narva (1924-1945)

When the Tartu Workers’ Commune murdered Bishop Platon (Kulbusch) in the cellar of the city’s credit association on 14 January 1919, they killed the last leader of the imperial diocese of Riga, a multinational jurisdiction that united Orthodox Estonians, Latvians, and Russians into a single church body. In its place, two institutions arose: the Estonian Apostolic Orthodox Church (EAOC) and the Latvian Orthodox Church, both of which defined their territorial limits in accordance with the borders of the new nation states of Estonia and Latvia. Both Churches were eager to assert their national characters, in part to distance Orthodoxy from the stereotype of being the ‘Russian faith’.

But what was to be done with the large numbers of Russian Orthodox, some native to the Baltics, others refugees fleeing civil war and repression in the Soviet Union? In Latvia, no special arrangement was created: the experienced and charismatic Archbishop Jānis (Pommers) used his considerable personal prestige among both Latvian and Russian Orthodox to negotiate disputes, at least until his assassination in 1934. In Estonia, however, a different path was chosen, namely the creation of distinct ethnic jurisdictions with some degree of autonomy. Thus, in 1924 a ‘Russian diocese’ was established, centred on the ancient city of Narva close to the Soviet border. Lasting until 1945, the eparchy catered for the religious needs of around 36,000 Russians, gathered into approximately 30 parishes and served by several dozen clergy [1]. But the diocese was often beset by scandal, particularly regarding the limits of its autonomy within the EAOC.

Russian Orthodox choir (early 1920s, probably Tartu) (ERA.5912.1.27.66)

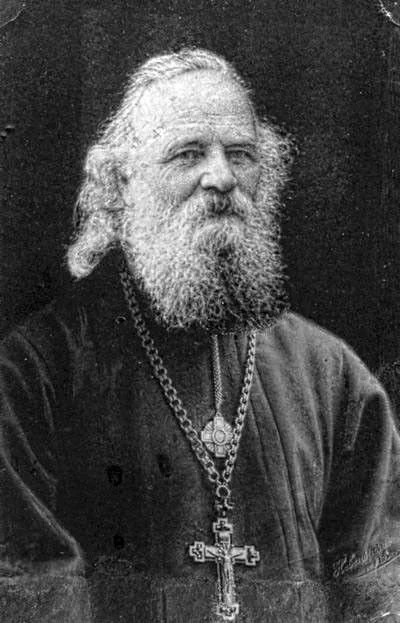

The idea of a distinct national unit for Estonia’s Russian Orthodox was already in play in 1919, despite Archpriest Aleksei Aristov’s complaint that ‘nothing is mentioned about Russian parishes, as if there were none at all in either Estonia or Latvia’ [2]. At a church congress on 18 March, it was resolved to include a Russian representative on the Provisional Diocesan Council of Estonia: elected was the aforementioned Aristov (1853-1931), rector of the Aleksandro-Nevskii cathedral in Tallinn, a job received following his retirement as rector and professor at the Riga ecclesiastical seminary. Known for his quiet, serious demeanour (he rarely smiled) and philosophical frame of mind [3], Aristov was to serve as dean of the Russian parishes. In the wake of the devasting wars in the region, the task confronting this sixty-six-year-old native of Samara was herculean: writing to Bishop Serafim (Luk’ianov) of Finland, he noted that he lacked even a list of the Russian parishes and clergy in Estonia and could not get access to the church archives to compile one [4].

Archpriest Aleksei Aristov

Aristov’s tenure was to last just over a year before he was engulfed in a major controversy. In June 1920, the Ministry of the Interior, acting on denunciations from both Russian and Estonian Orthodox figures, arrested Aristov, along with eleven other Russian clergymen and eight members of the laity: this included the exiled bishop of Pskov Evsevii (Grozdov) and Archpriest Vasilii Chernozerskii [5]. All these individuals stood accused of spreading information harmful to the republic and of ignoring the law [6]. The initial sentence was grim: the arrestees were ordered to leave Estonia forthwith or face internment. Immediate appeals brought a reprieve for most of the clergymen, who were detained at the Pühtitsa convent: due to his poor health, Aristov was permitted to live under house arrest at his wife’s holiday home in the picturesque lakeside town of Klooga.

The police’s case quickly fell apart due to the sheer flimsiness of the evidence. Aristov’s alleged crime was to have written a letter in October 1919 to the provisional government of the White Army then present on Estonian territory wherein he grumbled about the provisional Estonian Orthodox church administration[7]. Chernozerskii was condemned for having asked an acquaintance (a descendant of the early nineteenth-century Russian historian Mikhail Karamzin) to appeal to the Anglican archbishop of Canterbury for financial assistance [8]. But the consequences for some of those arrested were brutal. Father Petr Liubimov decided to return to the Soviet Union, where he was ultimately arrested and shot by the secret police in 1938. Aristov lost his job as rector of the Aleksandr Nevskii cathedral and was never able to regain it: he remained under a pall of suspicion, with his requests for Estonian citizenship denied [9].

It was, then, in a darkened atmosphere that the EAOC had its first council on 1-4 September 1920. As well as electing Aleksander (Paulus) as the leading archbishop of the Church, the council moved to elevate the Russian deanery once captained by Aristov into a diocese, one whose explicit aim was ‘the protection of the national independence of the church and ritual elements of Russian parishes’ [10]. The diocese would have its own suffragan bishop (junior to the newly elected Aleksander), council, and governing congresses, where both ecclesiastical and lay delegates from the parishes would regularly gather to decide policy for the 25 or so parishes classified as Russian. It would also possess its own financial resources, although it owed the EAOC overall an annual payment. Matters of church law and common interest would be resolved by the EAOC together in local church councils: similarly, appeals against the decisions of the Russian bishop and diocesan council would be handled by the archbishop and the EAOC’s Synod, where Russians were also given some representation. On the whole, this settlement provided the Russian parishes and clergy with a rather generous amount of autonomy: it was very likely modelled on draft laws about the cultural autonomy of minorities being considered in the Estonian parliament at the time.

But there was turbulence from the very start. The man elected as the Russian suffragan bishop was Ioann (Bulin), the abbot of the Pechory monastery. A fiery and energetic man, Ioann was not necessarily a bad candidate: he was a native of Võõpsu, thus commanding both the Estonian language and Estonian citizenship. However, according to canon law, he was too young to be a bishop, only twenty-seven in 1920: Patriarch Tikhon (Bellavin) of Moscow (at this point still technically the senior prelate of the EAOC) thus refused to consecrate him [11]. Consequently, when the diocesan council (known as the Ecclesiastical Council of Russian Parishes, ECROP) held its first meeting on 12 November 1920, it resolved to ask Archbishop Aleksander to take command, at least temporarily [12].

Tartu cathedral of the Dormition (Russian parish, early 1920s) (ERA.5912.1.25.68)

Another quandary was ascertaining precisely which parishes lay within the remit of the Russian Orthodox institutions: given that some parishes had split populations, how this was to be determined? As it emerged, only around 25 of the EAOC’s roughly 150 parishes were assigned to the Russian diocese: these were mainly based in Narva, Tallinn, Tartu, Pärnu, the Narva region, and the coast of Lake Peipus/Chudskoe. Thus, large Russian populations were excluded from the ECROP’s aegis. This was especially pertinent when it came to the parishes of the Pechory region, which were part of a deanery subordinate to the Synod, not the ECROP. A borderland area annexed by Estonia in 1920 under the terms of the Treaty of Tartu, the status of Pechory was highly sensitive: the government sought its incorporation into the rest of the Estonian state, but for the Russian minority it was regarded as a part of the lost motherland, a cultural stronghold of their national values, traditions, and tastes in the republic.

Finally, the composition of the ECROP was very narrow. Made up of nine men (four from the clergy, five from the laity), none of the members were ‘native’ Russian Estonians, but rather émigrés or residents in annexed regions. Only three of the nine resided outside Tallinn, and these three were very regularly absent from ECROP sessions (held a few times a month) due to the demands of travel. The preponderance of Tallinn was only accentuated by the fact that the capital’s four Russian Orthodox parishes regularly sent delegates to ECROP sessions to sit as non-voting representatives. Unsurprisingly, the laymen elected as ECROP members were typically prominent members of Russian society and minority associations. The politics and allegiances of these individuals sometimes left much to be desired. Take Boris Agapov, a former White Army diplomat, one-time ‘Russian national secretary’ within the Ministry of Education, and chair of the Aleksandr Nevskii parish council in Tallinn: in 1921, he was under political investigation for his connections to Russian monarchist groups [13].

Initially, these difficulties were not much in evidence: for most of 1921, the ECROP busied itself with the day-to-day business of corresponding with parishes, clergy, the Synod, civil associations, and government bodies. But 1922 proved a year of crisis for the new arrangement. The Synod’s decision to unilaterally impose the Gregorian calendar in place of the Julian provoked outrage from many Russian parishes, while the ECROP was annoyed that the Synod had not even deigned to consult them on the matter [14]. A chapel in the shipyards of Kopli was also a bone of contention: both the Synod and the shipyard’s owners (the Anglo-Baltic Shipbuilding Company, based in London) sought an Estonian clergyman (or at least one who spoke Estonian) to accommodate the new work force, but the parish and the ECROP desired the appointment of the refugee Russian priest who had been in place since 1919 [15].

Boris Agapov

Meanwhile, negotiations between the Synod and the Aleksandr Nevskii cathedral over the question of the temple serving as Archbishop Aleksander’s seat and the principal site of the EAOC were going badly. The cathedral, a flamboyant example of the Russian ‘national style’, sits on Toompea Hill, surrounded by government buildings: having Aleksander enthroned there would send a message about the literal and metaphorical centrality of Estonian Orthodoxy in the republic [16]. The parish council, however, was jealous of its rights and feared that Aleksander would force them to hold more regular Estonian-language services. The council was also furious they had not been permitted to reappoint Archpriest Aristov as the cathedral’s rector. Under the chairmanship of Boris Agapov from February 1922, the ECROP resolved to back the parish council to the hilt. The disputes between the Synod and the ECROP now became so acrimonious that regular business ground to a halt [17].

On 14-16 July 1922, delegates from all the parishes of the EAOC met in Tallinn at a local church council to find a way forward, but the mood on both sides was belligerent. Agapov demanded that the Russian parishes be separated entirely from most of the EAOC’s administration so that they would be united with the rest of the Church only through the person of Archbishop Aleksander [18]. When this suggestion was declined (Aleksander retorted that such autonomy had never been granted to Estonians or Latvians in the days of the empire), the Russian delegates walked out of the council, holding their own assembly and urging the ECROP to stand firm in the defence of their rights as a national minority [19]. Meanwhile, the church council proceeded to declare the Aleksandr Nevskii cathedral as the archbishop’s seat and to abolish the ECROP, effective from 6 August, to be replaced by a Russian deanery. Nonetheless, the ECROP continued to sit, refusing to recognise the authority of the Estonian Synod. The stand-off continued until September, when police closed the offices of the ECROP.

The closure of the ECROP temporarily denied Russian Orthodox institutional representation within the EAOC: the Russian deanery instituted in July 1922 never came into being. Thus, the Russians could do little to protest a momentous change: in 1923, the EAOC entered the jurisdiction of the Patriarchate of Constantinople, thereby ending its subordination to the Moscow Patriarchate. The relationship between the Estonian and Russian Orthodox remained tense, especially as calendar reform continued to incur spirited resistance in some Russian communities. Police suspicion of Russian church actors was also still high, with Ivan Egorov, a member of the Synod, providing reports to the police on some clergymen and the parish councillors of the Aleksander Nevskii cathedral, who obdurately refused to resign or be removed from their positions [20]. Boris Agapov almost lost his Estonian citizenship due to his monarchist connections and finally left for France in 1924 [21].

Archbishop Evsevii (Grozdov) of Narva (imperial-era photograph)

In early 1924, there were still fears that there would be a complete break between the EAOC’s Estonian and Russian wings [22]. However, in May key figures in the Russian National Union reached out to Aleksander (now a metropolitan) with a plan [23]. While the tone of the Russian leaders remained combative, Estonian representatives began to adopt a more reconciliatory approach, leading to the resurrection of the system instituted in September 1920: an autonomous Russian diocese headed by a bishop [24]. While some of the more radical Russian demands for autonomy were resisted, five Pechory parishes were handed to the diocese as a sop: thirty-one parishes now lay within the eparchy’s remit.

This time, Archbishop Evsevii (Grozdov) was nominated to lead the jurisdiction: a well-respected senior figure especially among the émigré clergy, Evsevii had, with the exception of his arrest in 1920, spent much of his time in Estonia living quietly in a small women’s monastic community in Narva. Before he could take up his position, he had to get Estonian citizenship and permission from the Moscow Patriarchate. While he waited, the Narva Diocesan Council (NDC), the executive board of the new diocese, started to meet from 18 September 1924: Evsevii was only able to begin active participation in early 1925.

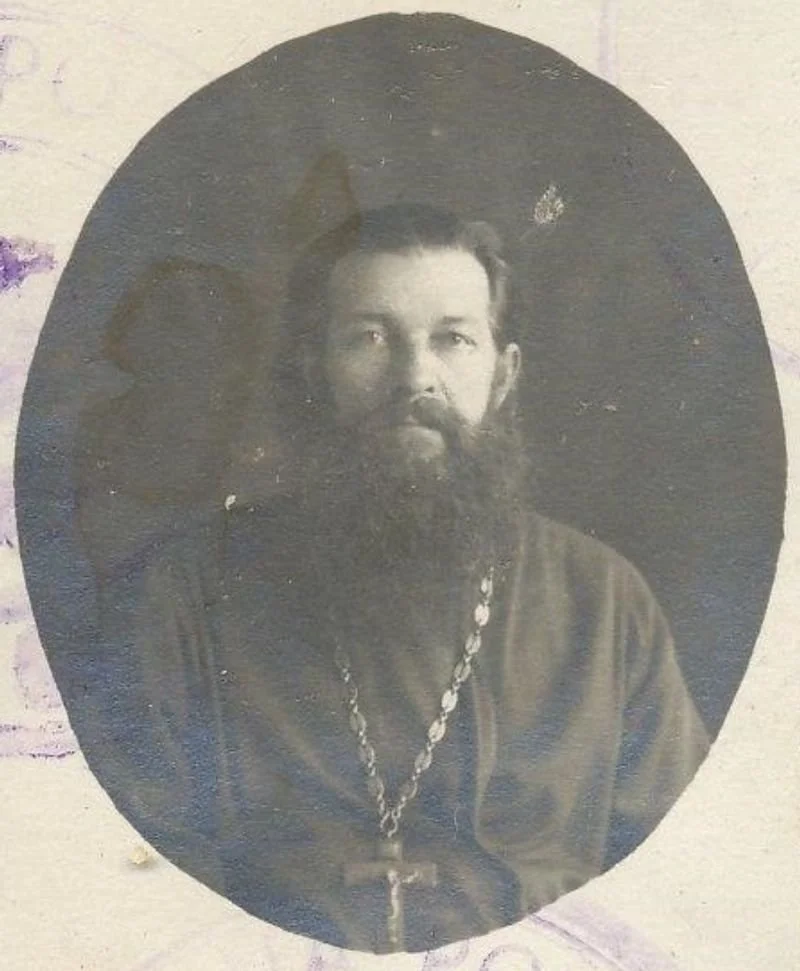

Archpriest Vasilii Chernozerskii, chair of the NDC

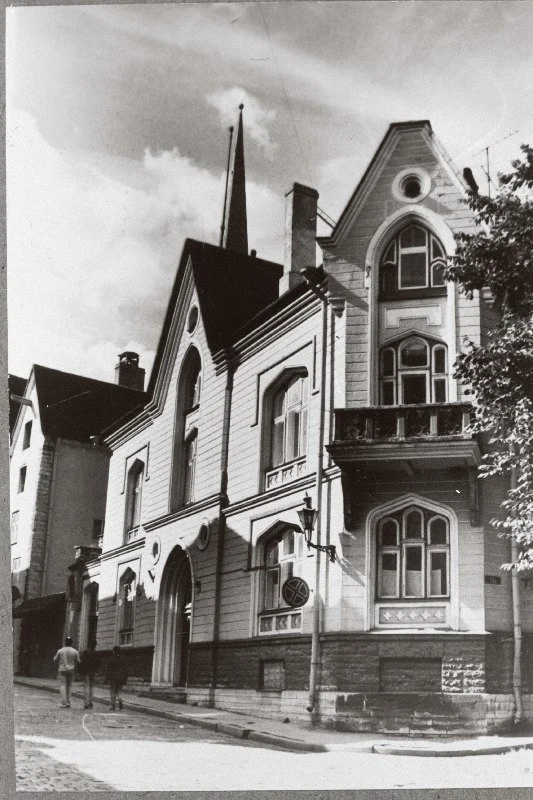

At the helm of the NDC were two men who were to control it almost without interruption until their deaths at the end of the 1930s: Archpriest Vasilii Chernozerskii (1868-1940) of the Tallinn church of St Nicholas served as chair, while Aleksei Khrenovskii (1860-1940), an expert civil servant in the postal system of both the Russian Empire and Estonia, acted as secretary. As with the ECROP, the NDC’s composition was dominated by the Tallinn émigré clergy: indeed, despite its name, the NDC was based in Tallinn, meeting once or twice a month in a handsome neo-Gothic apartment on Pikk tänav 73 that was later equipped with a small theological library.

The first hurdle the new diocese overcame was the reluctance of the government to recognise it: the Ministry of the Interior argued that neither church nor Estonian law allowed for bishoprics based on ethnicity rather than territory. However, following a change in government, Karl Einbund, the new minister, permitted the eparchy on the grounds that it was an internal church matter [25]. Next, the NDC had to take control over the paperwork amassed by Archpriest Konstantin Kolchin, who had overseen many of the Russian parishes as part of his role as the dean of Rakvere (a status he lost when the diocese came into being)[26]. Kolchin proved reluctant. Not only was he legendarily lackadaisical on the matter of church paperwork, but, a born-and-bred Narvan, he also thoroughly disliked many of the émigré clergy: he had denounced many of his colleagues for political unreliability in 1920.

Pikk tänav 73, Tallinn, home of the NDC

Then there were financial burdens. As of 1925, the diocese owed the Synod 83,000 marks in church tax, while it itself was owed 126,800 marks by its constituent parishes [27]. Given the lack of legal mechanisms in place to force parishes to pay their dues [28], this was a persistent problem for Narva diocese: over a decade later, in 1937, just under half of the diocese’s communities owed the eparchy 4876.20 crowns (or 487,620 marks in the pre-1927 currency), a sum that outstripped the entirety of the diocese’s budgeted annual income by around 1,500 crowns [29]. As such, there were virtually no means available to pursue any kind of ambitious project in the interwar era.

Furthermore, taxation was a bitter bone of contention between the NDC and its parishes, causing long and damaging clashes. To give but one example, the parish of Ol’gin-Krest continually refused to pay its tax arrears between 1925 and 1929: the struggle between the NDC and the parish council came to such a boil that it was only thanks to Archbishop Evsevii’s intervention that the NDC did not shutter the parish church [30]. Little wonder, then, that one journal opined, ‘the present diocesan council wields no popularity. It seems that there is not a single Russian parish that approves of its activities. From all sides (not only from the laity, but also often from the clergy), our editors receive declarations and complaints about this or that instruction from the diocesan council causing trouble and dissatisfaction in the parish’ [31]. Other commentators compared NDC members with Konstantin Pobedonostsev, the ultrareactionary bureaucrat-in-chief of the late imperial Russian Orthodox Church [32].

Orthodox church in Ol’gin Krest, 1919

Over the next several years, the diocese of Narva was broadly able to avoid further confrontations with the EAOC’s Estonian part, now reorganised into the diocese of Tallinn. In the meantime, internal tensions came to the fore. Already in 1926, there were moves afoot by Archbishop Evsevii to have the NDC and the diocesan congress moved from Tallinn to Narva, where Evsevii himself lived and worked: the prelate also took umbrage at the way in which the NDC presumed to dictate its will to him [33]. In response, members of the NDC complained that Evsevii looked on them like an imperial-era consistory under his thumb, not a democratically elected body with whom he had to cooperate [34]. They also denounced the moral qualities of the Narva clergy, calling one a drunk and another mercenary [35]. The matter came to a head at the diocesan congress on 17-19 June 1929, when Evsevii tried to pass a resolution about moving the NDC from Tallinn: in response, the Tallinn delegates threatened to slash salaries to NDC members if the relocation to Narva was approved [36]. In the face of such pressure, the congress demurred, leaving the NDC in Tallinn.

Further imbroglio was only averted by Archbishop Evsevii’s sudden death on 12 August 1929. With an election being possible only at a local church council (the next meeting of which was still a few years away), the diocese was temporarily handed to Ioann (Bulin), who had become bishop of Pechory in 1926. This was to prove a mistake. The state of Ioann’s Pechory monastery of the Dormition, a centuries-old hub of Orthodox religiosity, had become concerning to the Synod, since central oversight was lacking [37]. In 1930, an inventory commission to review all aspects of the monastery’s property and operations was established. Bishop Ioann and many of the other monks fiercely resisted the intrusion, believing that the effort to bring the monastery more firmly under the Synod’s control would result in the ‘estonianisation’ of an institution held to be of vital cultural value to the Russian Orthodox. A stand-off was thus triggered, with relations between Bishop Ioann and Metropolitan Aleksander plummeting as both men turned to the press to excoriate one another. Some of Ioann’s close associates found themselves arrested and expelled from the republic.

Bishop Ioann (Bulin) of Pechory

The impasse reached its peak at the local church council in June 1932, where the main question was the election of the bishop of Narva. The Narva diocesan congress had unanimously chosen Archpriest Anatolii Ostroumov (1861-1937), the rector of the Tartu cathedral of the Dormition. However, he was unacceptable to the church council: Ostroumov’s age, inability to speak Estonian, and fierce opposition to the Gregorian calendar were cited [38]. Instead, the Estonian delegates forwarded Ioann (Bulin). Strange on its face given Ioann’s increasingly rabid hostility to the Estonian parts of the EAOC, this ploy was designed to force Ioann to depart from the Pechory monastery: if elected as archbishop of Narva, he would have to take up residency in that city. Despite Ioann’s rejection of his candidacy, he was duly elected. Aggrieved that their own choice of bishop had been overridden, the Russian delegates abandoned the church council, the second time they had so in a decade: once more it was feared that the EAOC would be split in two.

That this did not happen is probably due to Ioann’s clear unsuitability as a figurehead and leader: finally forced out of the monastery by court order on 4 November 1932, Ioann took his struggle abroad, denouncing Metropolitan Aleksander before the patriarch of Constantinople and writing furious attack pieces in the press. With his actions impossible to defend, the NDC was obliged to condemn Ioann [39]. Meanwhile, Russian representatives in Tartu sought the course of reform, hoping to expand the diocese’s autonomy in order to defuse the ongoing situation and to prevent either the Synod or the church council from overriding the diocese’s choice of bishop again in the future [40]. Prominent in this project were political and cultural activists in the Russian minority, such as Professor Ivan Grimm (head of the Tartu branch of the Russian National Union) and Ivan Gorshkov, a member of the minority’s parliamentary faction.

However, despite some initial success in the negotiations, the political situation in Estonia soon froze the efforts. On 12 March 1934, Konstantin Päts held a coup d'état to stave off a fascist seizure of power. Päts’ authoritarian government instituted greater state control over churches; within the EAOC, new regulations were passed that took away powers from parish councils and handed them to the clergy and the Synod. It was clear that the times were unfavourable for the creation of autonomous institutions within the Orthodox Church. Indeed, some now called for the abolition of Narva diocese. This was resisted by Metropolitan Aleksander [41]. However, with the status of the Pechory region once again prioritised by the Päts regime, the five Pechory parishes handed to Narva diocese in 1924 were removed from its jurisdiction [42].

Clergy and laity of Narva diocese with Metropolitan Aleksander, 1930s (EAA.5410.1.36.1)

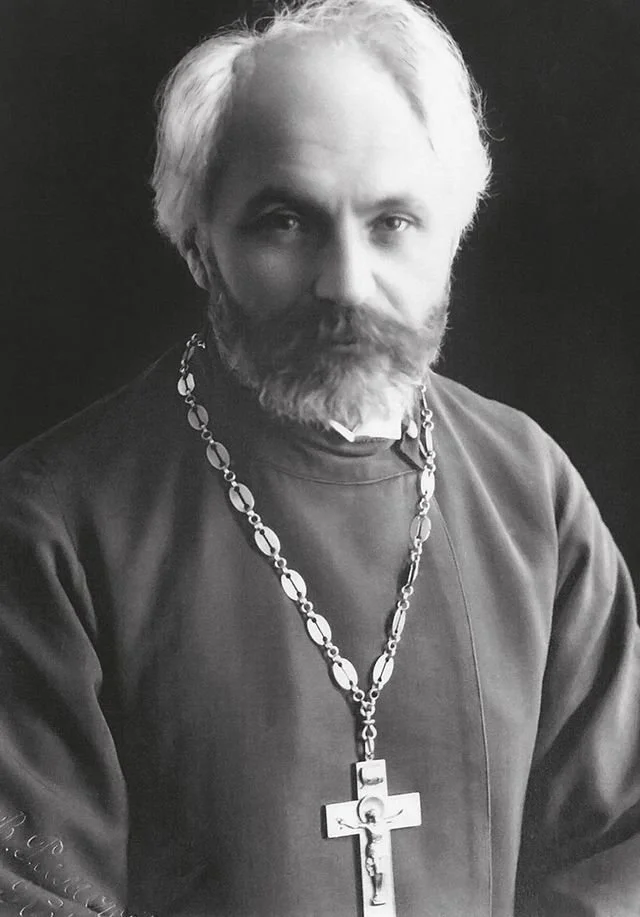

In 1935, the NDC sought to finally fill the episcopal vacancy haunting the diocese, proposing Archpriest Pavel Dmitrovskii (1872-1946) of the Narva cathedral of the Transfiguration: a clergyman from the imperial province of St Petersburg before fleeing the Bolsheviks in 1919, Dmitrovskii was esteemed for his social outreach, although the fact that he had been arrested in 1925 for anti-Estonian activities dimmed the glow of his candidacy. Nonetheless, when he was universally elected by a diocesan assembly in 1937, his nomination was accepted by the local church council [43]. Consecrated as Bishop Pavel (Dmitrovskii), he spent the next few years focusing his energy on improving the Church’s missionary activities and youth work: he also held regular visitations, hoping to restore discipline to the Russian clergy. His relations with the NDC seem to have smoother than those the board had with Archbishop Evsevii, perhaps in part due to the declining roles played by Chernozerskii and Khrenovskii, increasingly removed from NDC proceedings by age and illness. As one of his clergy later remarked, Pavel did not like to stand on ceremony: one of his favourite activities was to dress in normal clothes and leave Narva to walk in the fields alone, where he felt closest to God [44].

Bishop Pavel with graduates from the Narva émigré gymnasium (sitting second from the left), 1938

However, it was the years of the Second World War that shaped Pavel’s abiding legacy. During the first Soviet annexation of Estonia in 1940, the leaders of EAOC were obligated to travel to Moscow to beg forgiveness for having split from the Russian patriarchate in 1923. While Pavel protested he had only been a priest at the time and thus had played no role in the ‘schism’, he was still castigated by the patriarchate for having accepted episcopal rank from the EAOC. Nonetheless, once his penance was complete, Pavel was promoted to archbishop [45].

German invasion during the second half of 1941 interrupted Moscow’s resumption of its control over Estonian Orthodoxy. In a letter on 14 October, Metropolitan Aleksander restored the EAOC, once more breaking with the Moscow Patriarchate. But Pavel rejected Aleksander’s circular in 1942, demanding that all parishes of Narva diocese continue to act as if they were members of the patriarchate: in return, Aleksander censured Pavel [46]. This effectively split the EAOC in two during the Nazi occupation, with some parishes following Aleksander and others Pavel. What this schism looked like in human terms is revealed by an attempted memorial service in 1944 over the grave of St Mihkel (Bleive), one of the Tartu martyrs killed alongside Bishop Platon (Kulbusch) in 1919. Bleive’s family wanted the service to be performed by his son, a priest loyal to Metropolitan Aleksander, but the grave was situated in the Tartu cathedral of the Dormition, a parish that adhered to Archbishop Pavel. Pavel told the local clergy he had no opposition to the requiem being performed by Bleive junior, a position that provoked a strong reprimand from Pavel’s superior, Exarch Sergii (Voskresenskii), for potentially allowing a schismatic priest to serve in one of their churches [47].

Archbishop Pavel (Dmitrovskii) (1934, prior to becoming a bishop)

In the midst of all this chaos, the NDC ceased its operations for a couple of years, restored only in March 1943 [48]. It consequently worked to do what it could to appoint clergy to parishes bereft of pastors and ensure that the Russian population, now swollen by refugees and prisoners of war, received spiritual consolation. Managing around a dozen or so parishes and around twenty clergymen, the NDC was thus in place to witness the Soviet re-occupation of Estonia in autumn 1944. Metropolitan Aleksander and other members of the EAOC evacuated to Germany and then to Sweden, where they established a Church in exile. With communications now restored between the Moscow Patriarchate and the NDC, the former entrusted the latter with overseeing the liquidation of the EAOC’s Synod [49]. These were the NDC’s last actions: in April 1945, Estonian Orthodoxy was fully reincorporated back into the Moscow Patriarchate with the creation of the diocese of Tallinn and all Estonia, to be headed by Archbishop Pavel. The eparchy of Narva was abolished, resurrected only in 2009.

The minority question was nowhere easy to handle in interwar eastern Europe and the Baltics. Both Lutheran and Orthodox Churches had to deal with the issue, which frequently led to explosive political confrontations [50]. However, even when compared to other forms of ecclesiastical majority/minority management, Narva diocese was a failed experiment that produced strife rather than resolved it. Almost scuppered by two major clashes with the Estonian majority and constantly bedevilled by serious internal dilemmas, the diocese was often seized as a vehicle for the political ambitions of Russian social and cultural leaders while also being a magnet for criticism from Estonian national activists in the EAOC’s Synod. The decisions to locate its executive board in Tallinn and to staff it almost wholly with Tallinn-based émigrés only exacerbated struggles with parishes over resources and demands for parishioner control. While generally doing little to advocate for or defend ‘Russian’ aspects of church life, the diocese and its administration added another lay of costly bureaucracy. Although the Second World War was a punishingly cruel final test, the diocese ultimately led the way to the result it was supposed to prevent: the schism of Estonian Orthodoxy along mostly ethnic lines.

Notes

[1] There were 36,629 members of the diocese in 1931: Apostlik-õigeusuliste eestlaste kalender 1932 aastaks (Tallinn: Eesti Piiskopkonna Valitsus), 25. The number of parishes varied from 26 to 31 between 1920 and 1940. For the clergy, see J. M. White, ‘The Russian Orthodox Parish Clergy in Interwar Estonia: a Prosopography’, Journal of Baltic Studies (2025): 1–27 (first view).

[2] ERA.1.1.7084.6.

[3] G. Alekseev, ‘Pamiati protoiereia o. Alekseia Petrovicha Aristova’, Pravoslavnyi sobesednik, no. 3 (1931), 40-41

[4] ERA.1.1.7084.6.

[5] See S. K. Isakov, ‘K istorii konflikta v pravoslavnoi tserkvi Estonii. (Popytka vysylki russkikh pravoslavnykh sviashchennosluzhitelei iz strany v 1920 g.)’, Baltiiskii arkhiv: Russkaia kul’tura v Pribaltike, vol. 9 (2005): 134-162: T. Schvak, ‘Pravoslavnaia tserkov’ v Narve i ee conflict s Estonskim gosudarstvom v 1918-1920 gg.’, Sbornik Narvskogo muzeia, no. 22 (2021): 193-209.

[6] ERA.1.1.7084.146.

[7] ERA.1.1.7084.6.

[8] ERA.1.1.7084.66.

[9] ERA.14.12.731.

[10] EAA.1655.3.7.26.

[11] EAA.1655.3.248.74.

[12] EAA.1655.2.2570а.11.

[13] ERA.31.1.1245.3.

[14] EAA.1655.2.2570a.94.

[15] EAA.1655.2.2570a.64об.

[16] For more on the cathedral, see https://www.balticorthodoxy.com/cathedral

[17] EAA.1655.2.2598.41; EAA.1655.2.2570a.118.

[18] N. M., ‘Zasedaniia pomestnogo sobora Estonskoi pravoslavnoi tserkvi’, Zhizn’, no. 47 (16 June 1922), 2.

[19] EAA.1655.2.2611.56.

[20] ERA.1.7.38.

[21] ERA.1356.2.545; ERA.1356.2.296.

[22] EAA.1655.3.295 (unpaginated).

[23] EAA.1655.3.295 (unpaginated). See also ‘Tserkovnaia zhizn’’, Poslednie izvestiia, no. 153 (17 June 1924), 3; ‘Nashi polozheniia i programma. (K tserkovnomu s’’ezdu)’, Poslednie izvestiia, no. 197 (1920) (1 August 1924), 3.

[24] Polozhenie Narvskoi (Russkoi) eparkhii Estonskoi pravoslavnoi tserkvi (Tallinn, 1925), 78; ‘Russkaia eparkhiia v Estonii’, Revel’skoe vremia, no. 4 (11 May 1925), 3.

[25] P. Rohtmets, Riik ja usulised uhendused (Tallinn: Siseministeerium, 2018), 87-89.

[26] EAA.1655.2.2700.2-3.

[27] EAA.1655.2.2837 (unpaginated).

[28] Such mechanisms came into being only in the second half of the 1930s, when church leaders were given the right to use the police and courts against debtors.

[29] EAA.1655.2.895.87-87ob.

[30] EAA.1655.2.2674.38.

[31] ‘Ob ustroenii zhizni russkikh prikhodov’, Vesti dnia, no. 162 (960) (18 June 1929), 1.

[32] ‘Nel’zia molchat’’, Vesti dnia, no. 241 (331) (7 September 1927), 1; Prikhozhanin, ‘Vynuzhdennoe vystuplenie. Pis’mo iz Pernova’, Vesti dnia, no. 241 (331) (7 September 1927), 2.

[33] EAA.1655.2.2632.3-15ob.

[34] EAA.1655.2.2632.23.

[35] EAA.1655.2.2632.28.

[36] EAA.1655.2.2768.122-123.

[37] For the so-called ‘monastery war’, see J. M. White, ‘Orthodox Monasticism in Interwar Estonia and Latvia’, in J. M. White and I. Paert, eds., Baltic Orthodoxy: People, Places, Practices (Tartu: University of Tartu Press, 2025), 238-246.

[38] EAA.1655.3.360.23; 88.

[39] EAA.1655.3.360.177.

[40] EAA.1655.2.2889.13-25.

[41] ‘Tserkovnaia zhizn’ v Estonii’, Pravoslavnyi sobesednik, no. 5 (1937), 75-76.

[42] ‘Piat’ prikhodov perevedeny iz Narvskoi eparkhii v Petserskii vikariat’, Russkii vestnik, no. 32 (426) (28 April 1938), 3.

[43] EAA.1655.2.895.90-91.

[44] ‘Iz vospominanii o vladyke Pavle’, Estonskaia pravoslavnaia khristianskaia tserkov’, https://ru.orthodox.ee/articles/iz-vospominanij-o-vladyke-pavle/

[45] EAA.1655.2.2629.8-10ob.

[46] EAA.1655.2.2629.18-23ob; 25; 28.

[47] EAA.1655.2.2908.64.

[48] EAA.1655.2.2629.87.

[49] EAA.1655.2.2635.2.

[50] See, for instance, the political bust-up caused by conflict between Latvian and German Lutherans over the principal Lutheran cathedral in Riga: A. Brode, ‘National Activism and Symbolic Space: The Struggle for Riga’s Cathedral Church in 1931’, Journal of Baltic Studies, vol. 48, no. 1 (2017): 67-82.

author

James M. White

date added

20 January 2026

This article was supported by the Estonian Research Council grant PRG1599